The study included more than 200,000 men in the U.K.

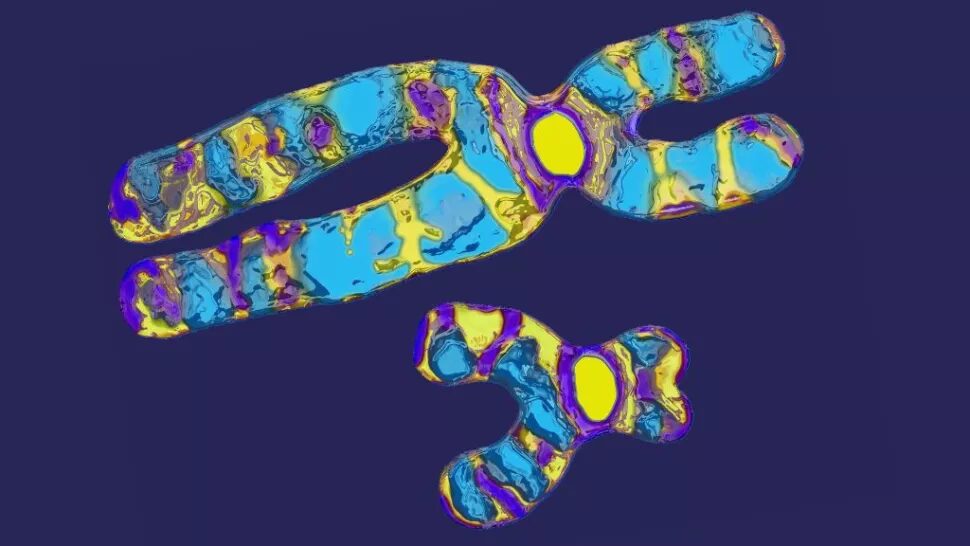

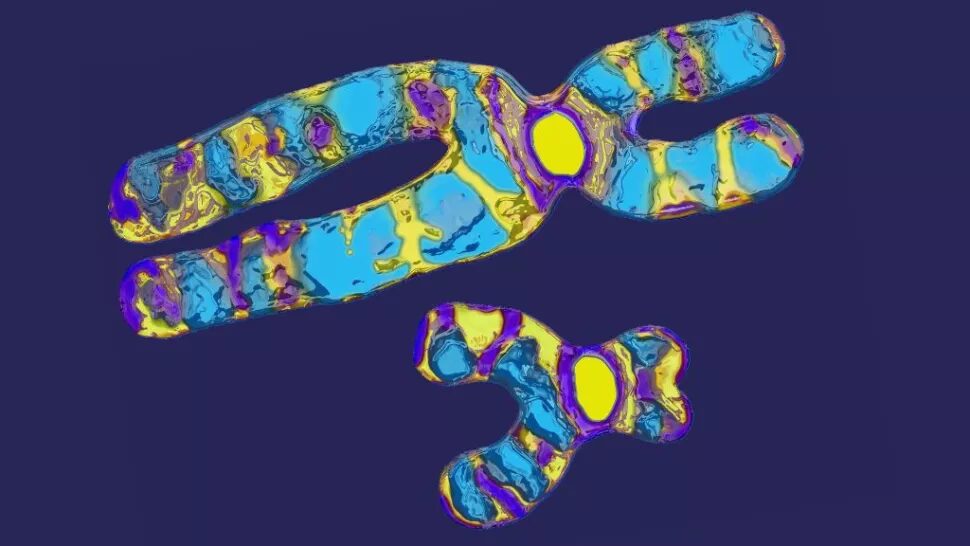

© BSIP / Contributor via Getty ImagesMost commonly, females carry two X sex chromosomes and males carry an X and a Y.

The research, published June 9 in the journal

Genetics in Medicine, included data from more than 207,000 men who provided information to the U.K. Biobank, a repository of genetic and health data from half a million U.K.-based participants. Typically, males carry one X- and one Y-shaped sex

chromosome in each of their cells, but among the study participants, there were 213 men who carried an extra X chromosome and 143 that had an extra Y.

Very few of these men either reported being diagnosed with a chromosomal abnormality or had such an abnormality noted in their medical records: Of the XXY men, only 23% had a known diagnosis, and just 0.7% of the XYY men had a diagnosis. (The potential symptoms of having an extra Y chromosome can be very subtle, which may somewhat explain the difference in diagnosis rates, according to the

Genetic and Rare Diseases Information Center.)

"We were surprised at how common this is," Dr. Ken Ong, a pediatric endocrinologist in the Medical Research Council (MRC) Epidemiology Unit at the University of Cambridge and a co-senior author on the study,

told The Guardian. "It had been thought to be pretty rare."

Previous estimates suggested that roughly 100 to 200 men out of every 100,000 are XXY, according to the

National Human Genome Research Institute, and an estimated 18 to 100 out of every 100,000 were thought to be XYY, the authors noted in their report.

Comment: See also: