"If it could be demonstrated that any complex organ existed which could not possibly have been formed by numerous, successive, slight modifications, my theory would absolutely break down."Such complex organs, not mentioning processes, exist in abundance, and they do absolutely break Darwin's theory down. His theory is about as broken as it gets, and this has been obvious for decades. Yet Darwinists refuse to accept it because they are more focused on maintaining their ideology and dogma than on the facts. In order to preserve the dogma, they usually ignore things that are inconvenient for them or misrepresent facts so that they can explain them away.

One of the many things that show the impossibility of organisms evolving step by step is the concept of Irreducible Complexity (IC). The point of the IC argument is that each part of a particular organ or process is necessary for the whole organ or process to work. If you take any one part away, the whole system stops functioning. It is not possible for parts of a system to be selected, step by step, when most of those steps do not produce a functional system. Several (or all of the) parts would have to evolve together, which contradicts the Darwinian model.

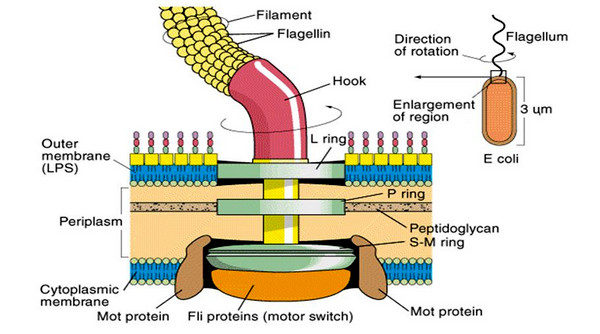

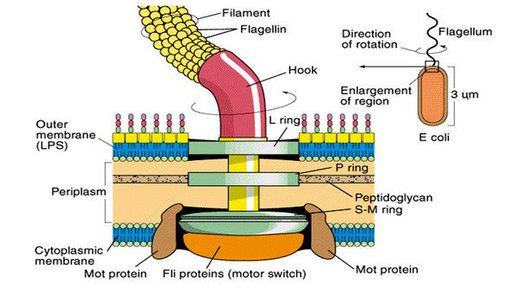

A well known example of such a structure is the bacterial flagellum, which you can see in the image at the top. Even just the fact that the simplest of organisms, a bacterium, possesses something this complex and sophisticated should give us pause. The flagellum is a marvel of engineering. It has about 40 parts that are all needed for the mechanism to work. It's similar to the structure of a man-made motor. You can probably guess that if you remove one part of a motor, it stops working. After all, if it worked without the part, why would the part be there in the first place?

Now imagine that the motor would have to 'evolve' one part at a time. It may be possible to assemble it one part at a time, but can you imagine that at every stage of the process you have something useful that works? In most of the stages, you'd just have a bunch of metal parts joined together but fairly useless because the thing can't perform any work. In the evolution of organisms along Darwinian lines, such stages are basically impossible. If a new addition isn't useful, or, to be precise, doesn't noticeably increase the organism's chances of survival, it won't spread in the population. Natural selection can't affect it.

One of the usual arguments of Evolutionists is that in the intermediate stages, the system or its parts can be useful for something else and thus improve survival. This is certainly possible in theory, but in practice, in 99% (or more) of all such cases, it would be extremely difficult at best to find any function for either the system or its parts. And if there was a function, there's a low probability that this system would later evolve into something with a different function. The logical direction of evolution would be to improve the function that exists. When a part is specialised in a certain way, any specialisation in a different direction would almost certainly decrease the quality of the original function. So while it is theoretically possible for this to happen now and then, it's untenable that it would happen in most, or all such cases, and when it comes to real life examples, proper explanations haven't been forthcoming.

If we look at the partially built motor, we see we may be able to use it as a hammer, for example. (And just about anything can be used as a paper weight, but how does that help us?) If we use this thing as a hammer, then an addition that will make it more useful is one that will make it a better hammer. But making it a better hammer is extremely unlikely to lead to a motor. And if the motor needs 50 parts, you have this problem at every single step. If at step 20, we have a hammer, and at step 21 a better hammer, how do you imagine we'll get to a step where the hammer stops being a hammer, evolves towards a motor but isn't a motor yet, and happens to have some other useful function? Suppositions of alternative functions are highly unrealistic and only reflect the desperate need to make evolution work at any cost. Requiring various different functions throughout the process actually makes the whole process far less likely.

There are certainly parts of the motor that can be used for other things, like screws. In the same way, biological structures can be made out of many things that, just like screws, are able to perform other functions. But you can probably see that the general usability of screws doesn't help us much with the intermediate stages of building a motor. Screws may be versatile, but it's the parts that are specific for a motor that are the core issue here.

A bicycle has many parts that can be useful for something else. Wheels can be used for many things, a saddle or seat exists on a horse or on the bus, a chain works in a chainsaw, brakes exist in a car, and so on. But how do any of those things help us 'evolve' a bicycle? They don't. Chainsaws don't 'evolve' into bicycles. They are separate designs. Usability of parts for other purposes doesn't help us evolve something specific.

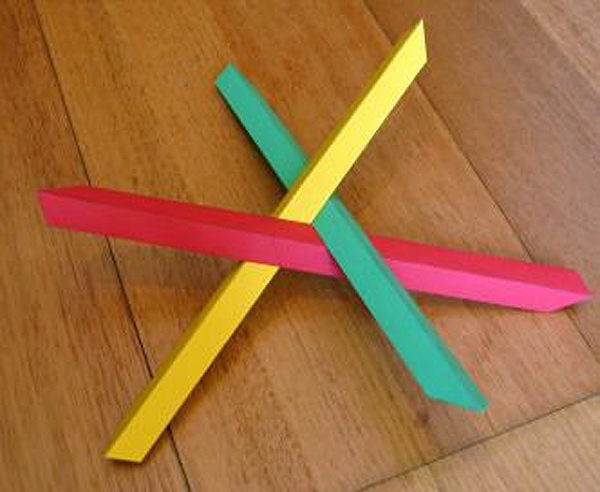

There can be functional subsystems, but that doesn't solve the problem. I'll use the toy in the image above to illustrate this. Let's consider the eight coloured parts to be the building blocks of the system, and a state where it 'works' to be any state where there's balance between the two sides. You can consider this irreducibly complex in the sense that if we take away any one part, it stops working - we lose balance. But you can see that if we take the same part away from each side, we have balance, and the system works. This would be an irreducibly complex subsystem. To 'evolve' from this subsystem to the complete system, we need two steps, and we need them to occur at the same time.

This is important to understand because Darwinists sometimes point to such a functional subsystem with the claim that this defeats irreducible complexity. This is a fallacy, as I just explained, and moreover, their task should be not so much to disprove irreducible complexity, but to show that the system can actually evolve step by step. This means that they must account for every single step. Pointing out that there exists some kind of a middle stage that works is great, but it doesn't disprove the irreducible complexity of the complete system, and more importantly, it doesn't prove evolution step by step. The toy in the image has four functional states, but between each two of those functional stages there's a stage that's non-functional, making evolution step by step impossible. You cannot add one part at a time and have balance at each step. And biology is infinitely more intricate than this.

There has been an attempt to show that the flagellum (in the top image) could evolve step by step. But all that was shown was one intermediate stage that worked. (And it later turned out that the flagellum had existed first, which shows how desperate the evolutionary explanations are.) We can now understand that this doesn't prove anything other than that this one stage works. Trying to prove that something works step by step by showing that one particular step works is a dead end. Where is the evidence of evolution from nothing to that intermediate stage, and where is the evidence of evolution from that intermediate stage to the whole system? There isn't any. For evolution to work, all steps between all known stages would have to be explained, and as far as we can tell, several steps at a time would be required in many stages to retain functionality. Even if there's only one stage that requires several steps to show improvement, evolution towards a complex functional system, step by step, is impossible.

Irreducibly complex systems can be whole organs or just small macromolecules composed of several proteins. Living organisms abound with them. I don't want to go into too much detail here, but if you're interested in more examples of irreducible complexity in biological systems, you can check for example this blog post.

Darwinist evolution requires gradualness, and every step must give us some degree of functionality for natural selection to be able to keep the additions in the genome. But putting the flagellum together, just like putting a motor together, is not a matter of degrees of functionality. You need at least a significant collection of parts for any functionality to appear at all. If adding one part doesn't significantly improve functionality, natural selection can't make any use of it.

So the idea that any kind of complexity can be overcome gradually is nonsensical. Of course it's possible to evolve something that has only two or three parts if each stage can be shown to be useful. But three parts isn't exactly complex, and the probability of something like this happening decreases exponentially with every new step. If the probability of one beneficial mutation occurring is one in a million, then the probability of two that work together occurring is one in a trillion. Above roughly three steps, the probabilities are so low that they can't be taken seriously even with 3 billion years at our disposal.

Darwinists are convinced that accumulation of small steps will lead to creating complex structures, or to anything they want, but this is extrapolating beyond reason. Adding small, simple things just increases the amount of small, simple things. Accumulation of random words does not a sentence make. You can stick a bunch of words together randomly, but to get meaning, you need intelligence. Some relatively complex things might be assembled step by step, but most complex things need several additions at a time to improve, often many. Natural selection is actually a limiting factor here, because every step has to increase usefulness.

We can take Lego as an example. You can certainly build complex things out of Lego one step at a time. But the condition for natural selection is that after each addition, the thing you're building must be better (more functional) than it was before. For most of the Lego pieces, one of them won't make any difference for the overall usefulness of the whole thing. And for living organisms, it actually has to significantly increase survival rate, which is a lot more difficult than just being slightly better in theory. And I've talked about the serious limitations of natural selection in my first article on Darwinism.

Darwinists have this irrational idea that if you just give it enough time, anything is possible. But that's like believing that if I keep randomly throwing stones all my life (or for thousands or millions of years), I will eventually construct the Taj Mahal.

One of the greatest obstacles to evolution is the need for new genes. There's a huge difference between mutating an existing gene and getting a new gene that will code for a new protein and will somehow have a control region on the DNA with instructions for the usage of the gene. If you want to evolve wings from nothing, you'll need a lot of new genes. Creating them randomly is virtually impossible. The idea that things can evolve gradually in very small steps ignores important biological realities. A new gene cannot evolve in small steps. You can't have half a gene. Either you have a whole working gene, or you have nothing.

The human genome has over 20,000 genes. To cover all species, present and past, evolution would have to have produced millions of new genes, yet evolving even one gene randomly is so ridiculously improbable that it's extremely unlikely it could happen during the 4.5 billion years of the existence of the Earth.

A new gene has to code for a new protein. This protein must have at least about 70 amino acids to be able to fold. If it doesn't fold, it's useless. Douglas Axe did experiments to find out what percentage of all possible proteins will fold. For a small protein of 150 amino acids, he calculated that only 1 in about 1074 amino acid variations would fold. So the very vast majority of proteins produced randomly would be completely useless. Finding one that works would be virtually impossible, even given an infinite amount of time.

Many proteins are thousands of amino acids long, requiring genes of specific sequences up to 100,000 nucleotides long to be created randomly. These lengths make the problem many orders of magnitude worse, and for most tasks in the organism, many proteins need to work together, which again compounds the difficulty. Consider that the task of protein translation requires over 100 proteins to do the job! Replicating the DNA requires over 30 proteins, the main one being longer than 1000 amino acids. They all have to be very specific and they have to fold in specific ways, so "evolving" them step by step is pretty much impossible. You need at least 70 amino acids to start with, and once the protein folds and performs a function, changing it to a longer one that performs better or does something else would be at least as difficult as creating a new one.

When Darwinists suggest how something like an eye could have evolved, they completely ignore biology. They think that mutations can just give them whatever they want, in small steps, and they only focus on the result (morphology), disregarding the processes required (molecular biology). They say the eye started with a light sensitive patch, as if that's a small step. It's not. It requires cells different to any that the organism has had so far, which requires at least one new gene, likely more. Yet this is completely ignored. And once you get to another new part, like a lens, you need new genes again. As David Swift writes:

"It really is time that biologists stopped proposing evolutionary scenarios that completely ignore genetic and biochemical implications. They have got to be taken seriously. A blind faith in the power of opportunistic genetic variability just will not do."Swift has much more to say about the difficulty of producing new genes by chance on his website, which is an excellent online resource for information about the problems of Darwinism in general.

While genes themselves are an insurmountable obstacle, you need not only a new gene, but also a control region that regulates how this gene is used. A gene without a control region is about as useful as buying a car and being told that the car is parked somewhere on this planet but no one knows where. Both the gene and the control region must be very specific and must arise at about the same time. How can this happen?

Darwinists say that the major source of new genes is gene duplication. Let's be honest - it's the only source they have, and it's a rather bad one. The idea is that a gene or a whole chromosome (or the whole genome) gets duplicated, and while one copy performs the old function, the other one can mutate and ultimately start performing a different function. This sounds plausible on the face of it, but how realistic is it really when we rely on biology rather than magic? Not very.

The idea that it will work as imagined is extremely naive. Let me relay a few quotes from the book Genetic Entropy by John Sanford:

Let us consider the human population. Are there any polyploid humans? Of course not. Duplicating all the human genome is absolutely lethal. Are there any aneuploid humans? Yes there are-a significant number of people have one extra copy of one chromosome. Do these individuals have more information? Most emphatically they do not. While aneuploidy is entirely lethal for larger chromosomes, an extra copy of the smallest human chromosomes is not always lethal. Tragically, the individuals who have this type of "extra information" display severe genetic abnormalities. The most common example of this is Down's Syndrome, which results from an extra copy of chromosome 21. There are countless smaller duplications and insertions which also have been shown to cause genetic disease.Even in the best-case scenario, where nothing gets completely broken right away, there's hardly any potential for improvement. When you duplicate a gene, the production of the associated protein will increase. But because organisms are quite finely tuned, this increase is far more likely to be detrimental than beneficial. But suppose it's neutral. What then? Naturally, mutations make genes degenerate, and it's natural selection that prevents this from happening too severely. But because there are two copies, degeneration of one of them poses no problem for survival, so it can degrade rather quickly into a useless pseudogene.

[...]

It is often claimed that after a gene duplication one gene copy might then stay unchanged while the other might be free to evolve a new function. But neither of these events is actually feasible. Both copies will degenerate at approximately equal rates due to the accumulation of near-neutrals [near-neutral mutations] ...

[...]

The simple-minded notion that merely duplicating a gene might be beneficial is biologically naive.

[...]

Lastly, actual gene duplications not only mess up their own expression, they routinely mess up the expression of other genes. Much of my own career was spent in the production of genetically engineered plants. Industry and academia spent over a billion dollars in this endeavor. What was quickly discovered was that multiple gene insertions consistently gave lower levels of expression than single gene insertions. Furthermore, the multiple insertions were consistently less stable in their expression ...

The idea that mutations will cause a change in the resulting protein that will be beneficial is, again, pure fantasy. Changing even one amino acid in the sequence is more likely to prevent the protein from folding (and thus become useless if not detrimental) than do anything else. It would be extremely difficult to get a protein that works at all, much less one that's somehow better. And the chance that it would evolve into a longer functional protein is essentially nil. We're dealing here with probabilities of one in 101000 and worse. And these odds would have to be overcome millions of times for evolution to be true. In his book Signature in the Cell, Stephen Meyer explains in detail many of the relevant calculations. Even with the power of the whole Universe and 13.8 billion years available, the probability of creating a functional protein by chance is nil.

Let us note what the observed reality is. We have seen adaptation by mutations in nature and in labs. But virtually every such example is a mutation of an existing gene. The same is, of course, true of dog breeding. Even if humans help the process, there's no way to get new genes, so any results arise from the present variations. The Darwinist model works for adaptation by modifying the existing information, i.e. the present genes. No new genes are created by random mutations, thus natural selection cannot preserve them. They simply don't exist.

It is time to accept that random mutations and natural selection only have a very limited scope, and for anything complex that requires new genes, something else must be at work.

Comment: This article is the second in a series. For part 3, go here:

Evolution - A Modern Fairy Tale