Today, in the background of the risk of world conflict and threat to health and our way of life arising from Covid-19, it's never been more important to be sceptical and understand evidence.

Earlier in my career, I used to adjudicate financial disputes between two parties, weigh up the evidence, and decide the most likely scenario.

So, in terms of what's going on in the world, I'm interested in narratives which are open to challenge and the thinking and motives of those in power, the media, and experts behind them. And particularly how the public watching and listening process these messages.

First, before reading on, watch this clip, which I think is hilarious and vaguely relevant to what I'm going to say.

For those not familiar with the actors, this was a press conference held by Eliot Higgins of Bellingcatin 2018. Bellingcat is an Atlantic Council-funded online investigative website which has looked into the shooting down of the MH17 passenger plane, alleged chemical attacks in Syria, and the Sergei Skripal incident.

Graham Phillips, who crashed the event, is an independent UK journalist. He was there to ask Higgins what evidence he had for concluding Russia was responsible for the Skripal incident.

Someone unfamiliar with the background watching the clip might view Phillips as an amusing but disruptive, perhaps even unhinged, character who should have been escorted away by the police sooner. Yet appearances can be deceiving. Those aware of Bellingcat, Higgins, and their highly suspect investigations, will know that the some of the questions Phillips was posing about the evidence for Skripal were pertinent.

Secondly, many people think they are not qualified to research or question the politics or science behind government decisions.

I can understand people with busy lives accepting narratives about events in far-away parts of the world. But Covid-19 should really change that given the impact that lockdown may have on our lives for years to come.

This is what Lord Sumption, former member of the English Supreme Court, said about Covid-19 on BBC Radio 4 recently:

"What I say to them is I am not a scientist but it is the right and duty of every citizen to look and see what the scientists have said and to analyse it for themselves and to draw common sense conclusions. We are all perfectly capable of doing that and there's no particular reason why the scientific nature of the problem should mean we have to resign our liberty into the hands of scientists. We all have critical faculties and it's rather important, in a moment of national panic, that we should maintain them".Lord Sumption is right. I often didn't have expert knowledge of the area I was adjudicating on. It wasn't necessary as we would rely on expert evidence, typically independent or from two sources. What I did was just weighing up information -- an ability most of us have when applying ourselves.

Evidence comes in many forms: testimony, circumstantial, documents, and research or expert studies.

Below are some established concepts of assessing evidence as well as some pointers about the reality of today's global scene that's relevant when reviewing sharply conflicting narratives.

History And Track Record

This is a good initial indicator. Similar to detectives investigating a murder, they will be guided towards a suspect who has a criminal record.

In the case of Western governments, their advisors, and media, a look at their previous record on a whole range of important issues will show they've been wrong.

However, we should be mindful that just because they've always been wrong, that it doesn't follow they are this time around.

For example, based on their past track record, we should certainly view governments' response to Covid-19 with scepticism initially and ask questions. The information which flows from this and other material will make up the main body of evidence.

Onus Of Proof

Taking Covid-19 as just one example, it amazes me when someone says, "you seem to think lockdown is not necessary, it states on the news that it's working, so what proof do you have that it isn't?"

I probably don't need to elaborate on this lazy thinking except to say that the onus is on those who assert to prove. So, the duty is on the government to show that lockdown is working by directly reducing infection, and most importantly, is necessary in the big scheme.

The media is a main channel to communicate such evidence, but statements of "we don't know" or "it's too early to tell" or "trust the science", contradictions, and scare stories have been typical of the entire Covid-19 response.

Meanwhile, many sceptical experts and independent commentators have brought much to the table in terms of scientific studies and the questioning proportionality of lockdown measures.

The sceptics as yet have not had the same air-time to put forward their case. But people need to remember that the government has not discharged the onus of proof over Covid-19, and historically, rarely do over other events.

Motives

We go back again to our detectives. Who has most to gain from pushing a certain narrative? With Iraq, there were clear agendas in Washington to go to war, so much so that stories appeared in the press of links between Saddam Hussein and Al Qaeda. When this nonsense was dismissed, we moved to the threat of WMDs. We went to war out of a determination by Bush and Blair.

Today, I believe that the UK government is realising their lockdown response was driven by blind panic after receiving incorrect advice on potential mortality rates from their scientists. So, their main motive now is to prevent an angry backlash against the damage caused by lockdown.

Mixed up in all events from Iraq to Covid-19 are the combined interests of numerous parties such as NATO-funded NGOs and investigative sites such as Bellingcat, career journalists, arms industry lobbies, and big pharma. These vested interests include money, career advancement, power, and ideology.

For example, in deciding whether to get involved in Syria, selfish interests worked together. This is why one war after another has been a disaster.

Independent journalists and activists don't generally have the same motivations and therefore their opposition to their government's Syria policy is based on the horror of the destruction and threat to world peace.

Thus, understanding the main players and their motives is crucial to understanding evidence.

Tactics

I recall when adjudicating disputes, the lengths one party would go to, to mislead or pressurise me.

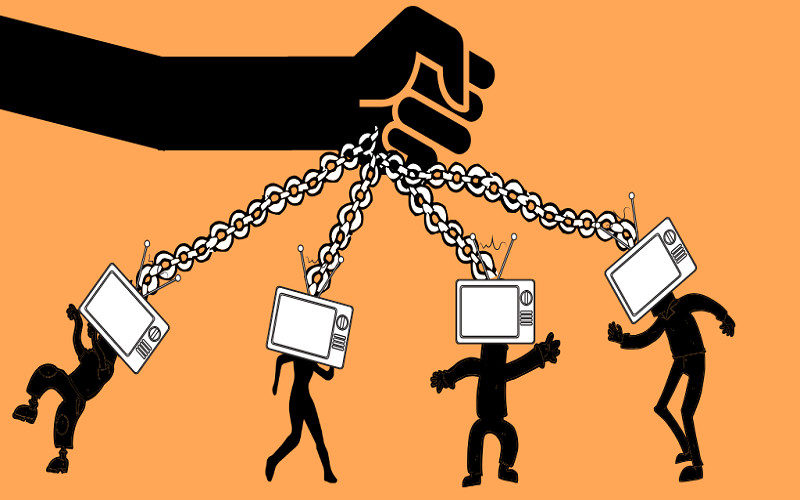

The government, in pushing the narrative of the day, is no different, and has many tools in its armoury, not least a compliant media.

Blaming others, dumbing-down debate, and distracting their audience towards less important issues are classic tactics. For example, when the Covid-19 debate should be about whether lockdown is proportional and necessary, the media focus on scare stories, lack of equipment for health service staff, and blaming China.

The government and media also build a 'unifying' theme, encouraging weekly clapping for health workers and constant TV adverts telling us to "stick together to see it through".

But the mask slips when dealing with the dissenters. Heavy-handed policing of lockdown and outright censorship of those who question the necessity for lockdown, even extending to the views of respected but non-government experts.

Twitter mobs sucked into the frenzy of fear and the new 'unity' emerge to smear and insult those questioning the government position.

These tactics have been used prior to every war and during every crisis, only for the narrative to later collapse.

A sign that these people are wrong is that if their position had merit, they wouldn't censor and would debate.

One of their tactics is to label anyone who questions the prevailing narrative as "conspiracy theorists". Unfortunately, some dissenters, rather than stick to the position that the government has serious questions to answer, go on to speculate and develop theories which can't be proven. This provides the opportunity for those pushing official narratives to dismiss powerful arguments based on one error or supplementary theory.

Experts Aren't Always Right

I know from experience that experts are often wrong -- possibly due to a bias, an under- or over- emphasis on certain evidence, a method, or an inability to think a little outside of their field. The results can be seen in all professions, for example, in miscarriages of justice and the experts which advised governments on WMDs, chemical weapons use in Syria, and Covid-19.

As such, the government messages of "trust the experts" should be treated with caution.

Prejudice

We all have conscious and unconscious prejudices or accepted viewpoints based on peer pressure. One example which comes to mind is among some even in alternative media circles. They say, "Assad is a brutal dictator, but didn't gas his people". They've looked at the evidence to establish the latter, but have unconsciously swallowed the unsubstantiated media propaganda on Assad as a person.

Peer pressure, pre-determined positions, and ideology are barriers to independent thinking. But just being mindful of these pitfalls when reviewing evidence helps to get to a more open-minded mindset.

Final Thoughts

To those who've researched and studied evidence and applied this to global events, it's apparent that mainstream thinking at all levels doesn't resemble the reality. Nowadays, a mainstream position on the most important events can be ripped to shreds.

Covid-19 and lockdown are by far the biggest event which has affected all our lives. Therefore, I'd expect the important questions about the real risks and proportion to gather pace.

In the meantime, we should spend the time in lockdown looking at the evidence in the round.

Reader Comments

to our Newsletter