The agents had played him a scratchy recording of a conversation he'd had with a friend at a restaurant in Eatontown, N.J. Both men found it strange when a pot of hot tea arrived at their table without their having ordered it, but only later did Su, an award-winning scientist for the U.S. Army's Intelligence and Information Warfare Directorate, form a hypothesis. He thinks the teapot was bugged.

On the recording, Su says, he can be heard telling his friend in Chinese to always use English when they spoke on the phone, because the government was monitoring all his calls. He warned that "when you work with us, you need to be careful." Su says the FBI demanded to know if "us" was a reference to Chinese intelligence. No, he answered, "us" simply meant his employer, the U.S. Army.

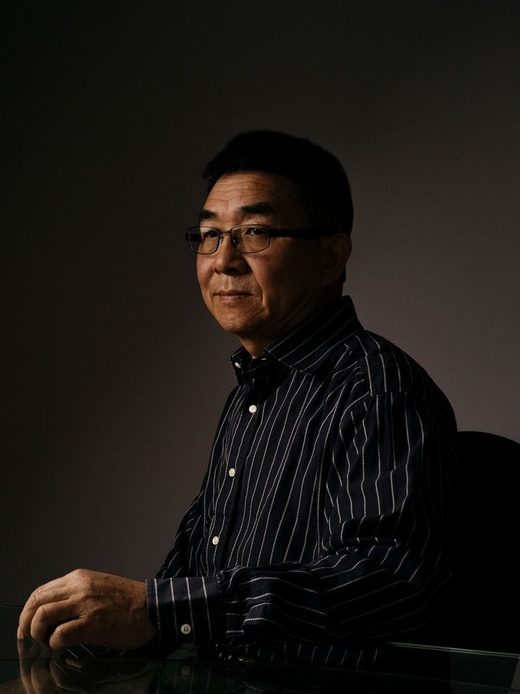

Nevertheless, questions about Su's loyalty would propel a multiyear investigation that in 2016 prompted the U.S. Department of Defense to revoke the top-secret security clearance he'd held for 24 years. He retired the next year: humiliated, angry, and, the Pentagon later admitted, completely innocent.

The short, bespectacled scientist who loves to kayak, garden, and play the piano now divides his time between Maryland and Florida with his wife of 32 years, Elaine, a retired branch chief for a different Army communications lab. The government's case against him amounted to a tempest in a teapot, Su says, if not a listening device as well.

Su's ordeal reflects how the U.S. government's distrust of China, which flared during the Obama administration and erupted openly during President Donald Trump's trade war, has mutated into distrust of Chinese Americans. Signs of this heightened scrutiny emerged in July when FBI Director Christopher Wray told the Senate Judiciary Committee that the bureau is investigating more than 1,000 cases of attempted theft of U.S. intellectual property, with "almost all" leading back to China. Last year the U.S. National Institutes of Health, working with the FBI, started probes into some 180 researchers at more than 70 hospitals and universities, seeking undisclosed ties to China. Some of the suspected scientists were instructed by their associates in China to conceal their connections to the country while in the U.S., says Ross McKinney, chief scientific officer for the Association of American Medical Colleges. "The presumption of trust is blown by the fact that there's a systematic approach to lying," he says.

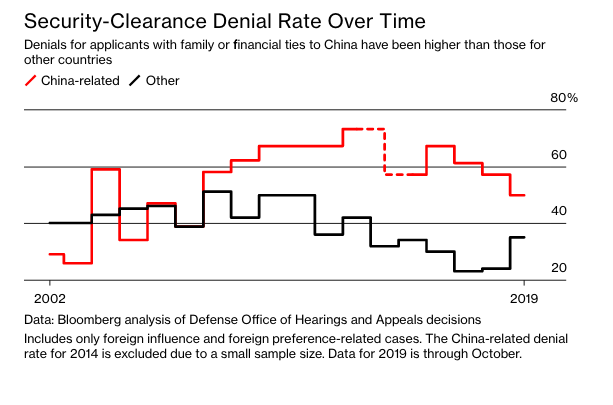

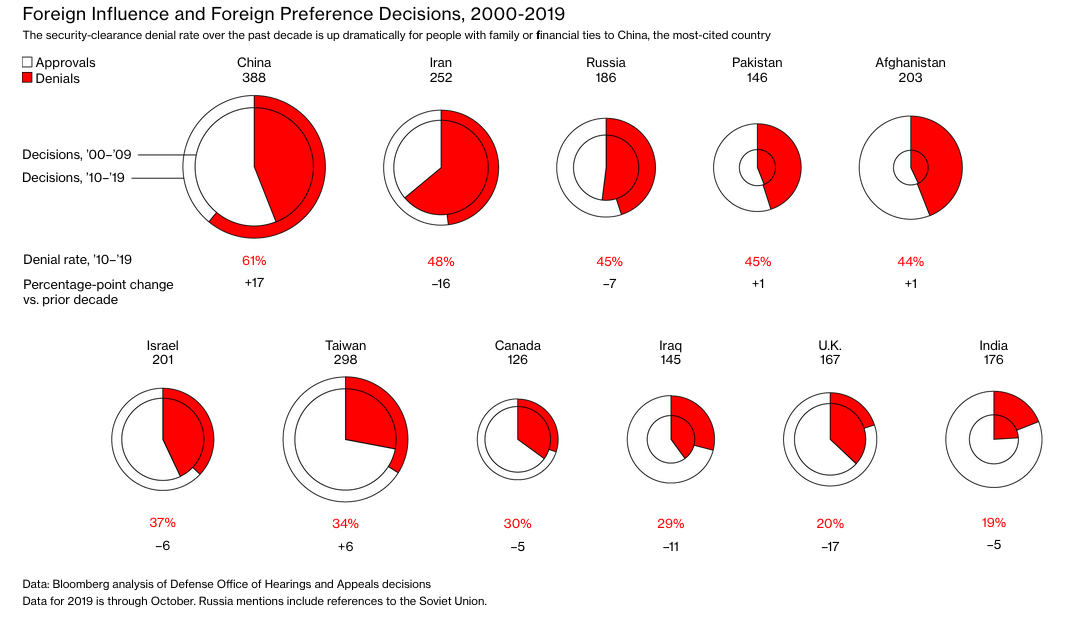

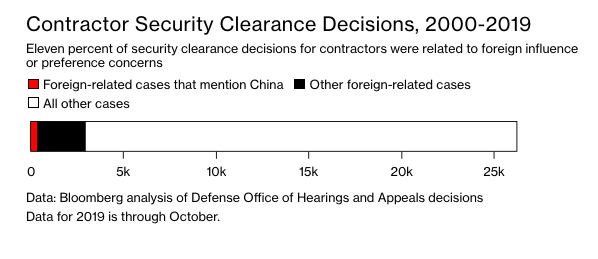

A Bloomberg News analysis of more than 26,000 security clearance decisions for federal contractors since 1996 demonstrates another facet of the government's steep loss of faith in Americans with ties to China. From 2000 through 2009, clearance applicants with connections to China — such as family or financial relationships — were denied Pentagon clearances at the same rate as applicants with links to all other countries: 44%. But from 2010 through Oct. 31 this year, the China-related denial rate jumped to 61%, and the rate for all other countries fell to 34%. In other words, more than three-fifths of applicants who have family or other ties to China are rejected for security clearances to work for government contractors, while two-thirds of applicants with ties to other countries are approved.

Eleven percent of security clearance decisions for contractors were related to foreign influence or preference concerns

Data: Bloomberg analysis of Defense Office of Hearings and Appeals decisions

Data for 2019 is through October.

Even people with ties to Iran and Russia, among the most often rebuffed applicants in the early 2000s with denial rates of 64% and 52%, respectively, have had their rejection rates fall since 2010 to 48% and 45%. That compares with a 17-point jump in the rate of China-linked denials. Some attorneys who specialize in helping applicants get security clearances say they won't accept Chinese American clients anymore for fear of wasting their money.

"It's gotten to the point that some of my clients won't even call or visit their own mother in China to avoid having to disclose the 'foreign contact,' " says Alan Edmunds, who's practiced national-security law for 41 years. "I've never seen the DoD or other three-letter agencies in such a heightened state of sensitivity."

Su's case tracks the rising alarm — and alarmism — over the past decade. Su, 67, earned his undergraduate degree in China and his doctorate in electrical engineering at City University of New York in 1992. From 1994 until he retired, he worked at the Army's Intelligence and Information Warfare Directorate, known as I2WD, a stealthy lab that develops electronic-warfare systems to enable military forces to communicate and eavesdrop without enemy interference. An elected fellow of the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers, Su has 170 scientific papers and 35 patents in his name. His mentor and frequent collaborator, I2WD's former chief scientist John Kosinski, wrote in a 2015 job recommendation that Su had achieved "an almost unheard-of distinction: His personally developed, Army-owned software product was adopted for use within certain offices of the [National Security Agency]."

In 2011, after 17 years of routine, periodic reviews of his security clearance, Su started receiving frequent visitors to his office from the FBI and U.S. military intelligence. Eventually, he says, they demanded that he confess to spying for China lest he end up "like the Rosenbergs." When Su insisted he was a loyal American, FBI agents placed him under surveillance and threatened to have a SWAT team arrest him in his home in front of his family, he says. "It was an opportunity to catch a big fish and make their careers," Su says.

In 2005 the bureau introduced an initiative that used U.S. Census data to map U.S. neighborhoods by race and ethnicity to guide FBI surveillance of potential terrorists and spies, German wrote. In 2009 the bureau justified opening such an assessment of Chinese communities in San Francisco on the grounds that organized crime had existed "for generations" in the city's Chinatown, according to an FBI memo obtained in 2011 by the American Civil Liberties Union.

FBI internal training materials released at the same time featured presentations on "The Chinese," which were full of generalizations about Confucian relationships ("authority and subordination is accepted") and the Chinese concept of saving face.

"The training is a form of othering, which is a dangerous thing to do to a national security workforce learning to identify the dangerous 'them' they're supposed to protect 'us' from," says German, now a fellow at the Brennan Center for Justice at New York University Law School. "Even the title, 'The Chinese,' imagines 1.4 billion people sharing the same characteristics. It seems more likely to implant bias than to educate agents about the complex behavior of spies."

LaRae Quy, who worked as an FBI counterintelligence agent for 24 years before retiring in 2006, says she believes the generalizations are justified. People from China, unlike Russians, maintain close ties to the homeland that make them particularly vulnerable to recruiting as spies by Chinese intelligence, she says. "You're American-born, but you're Chinese at heart," says Quy, who is now an author and executive consultant.

When people who want to work for the Defense Department, either as contractors or employees, are denied security clearances, they can ask the Pentagon's Defense Office of Hearings and Appeals for an administrative review. DOHA's decisions regarding employees, such as Su, are kept private. But the agency publishes its decisions on contractors, with names of applicants and witnesses redacted. Bloomberg's analysis of clearance rates is based on DOHA's database of decisions.

DOHA judges apply 13 federal guidelines to determine trustworthiness. Most are common sense, such as an applicant's drug and criminal history, or whether any debts could motivate the sale of secrets. They also consider each country's espionage risk. Bloomberg examined two key guidelines, "foreign influence" and "foreign preference," which ask in essence whether applicants have friends, family, property, or other foreign ties that could compromise their loyalty to the U.S. Federal law stipulates that the benefit of the doubt lies with the government: "Any doubt concerning personnel being considered for access to classified information will be resolved in favor of the national security."

In a representative DOHA decision last year, the 61-year-old founder of a machinery-design company sought a security clearance to work on his company's defense contracts. He immigrated to the U.S. from China in 1985, earned a doctorate, became a U.S. citizen, and has two grown daughters born in America. He also has real estate, retirement accounts, and substantial financial interests in the U.S., wrote DOHA Judge Noreen Lynch. She noted that there's "no evidence" he or his father and two sisters in China were ever approached for sensitive information by Chinese intelligence agents. And though the businessman used to visit and send money to his 90-year-old dad annually, he stopped that a few years ago as a result of his security clearance investigation.

Siding with the Pentagon, Lynch took "administrative notice" of a U.S. finding that China and Russia are "the most aggressive" sponsors of economic spying. She found the "Applicant's close relationship to his father and sisters, who are vulnerable to potential Chinese coercion, outweighs his connections to the United States." Clearance denied.

The idea that having friends or family in China makes Chinese Americans vulnerable to coercion by Chinese agents, directly or through their loved ones, is a premise of most of DOHA's China-linked denials. In Lynch's 12-page ruling, the word "coercion" appears 11 times.

National-security lawyers question that notion's evidentiary basis. "I dare say you will find no evidence of this threat being real. Logical? Yes. Real? No," says Mark Zaid, who represents numerous security clearance applicants. (He's also co-counsel for the Ukraine whistleblower.)

The coercion concept is a holdover from the Cold War, when Soviet-bloc governments blackmailed their own citizens to get family members to spy for the Communist regimes, according to a 2017 report published by the Pentagon's Defense Personnel and Security Research Center. "Threatening to harm a person's relatives living under Communist control in Eastern Europe, or threatening to publicly reveal one's sexual identity, have not been effective coercion strategies" since the fall of the Berlin Wall, wrote the report's author, Katherine Herbig of Northrop Grumman Technology Services.

Of the 141 U.S. convictions for espionage and related crimes from 1980 through 2015 — 22 of them involving China — coercion was not a "strong motivation" in a single case, the report said. At least 12 of the 22 people convicted of spying for China weren't ethnic Chinese, according to Jeremy Wu, a retired federal official who has analyzed China-espionage cases for an academic research paper.

For Wei Su, the Army engineer, the trouble began in 2011, when he was approached by a stranger at his hotel while attending a technical conference in Auckland. The man said he was with Taiwanese intelligence and asked Su if he'd given information to China. Su brushed him off and reported the incident immediately to his supervisor in Maryland.

When he returned to the U.S., he says, a military intelligence agent told him he must have done something wrong to warrant the "foreigner's" approach and urged Su to confess. Su says he has never had any improper contact with any Chinese official.

Over the next 21 months, Su endured six aggressive interrogation sessions, alternating between military intelligence agents and the FBI. They pressured Su to admit to working for China, which he steadfastly denied. They accused him of inventing a technology for embedding digital watermarks in DVDs not for the commercial purpose of protecting intellectual property, as stated in his research, but rather to spirit secrets to China. They said a friend of Su's told them Su had contacted Chinese officials while visiting his dying father in China in 2007, a lie, Su says. Carol Cratty, an FBI spokeswoman, said in an email that the bureau doesn't comment on specific cases, but also that it doesn't "initiate investigations based on an individual's race, ethnicity, national origin or religion."

According to Su, FBI agents threatened to knock down his door and arrest him at 5 a.m. and hound him until his health gave out. They asked his relatives, friends, and neighbors if he was a spy, Su says, and many stopped talking to him. He says interrogators from military intelligence warned him multiple times that the punishment for espionage was the electric chair. (The federal government hasn't used the chair for executions since 1957.) They asked, again and again, "Why would you work for the U.S. government when you can get a great job in private industry?" Su says. He told them that the Army scientists who recruited him had convinced him that a government lab offered the best opportunities to do advanced research.

Su says the FBI believed he was slipping secrets to Mengchu Zhou, an engineering professor at the New Jersey Institute of Technology in Newark, who would pass them on to the Chinese consulate in New York. At the time, Su ran a government contract with Zhou to do unclassified research on decoding signals.

Zhou says he never participated in any espionage, and that the FBI questioned him more than 10 times about Su, as well as about his own frequent social and professional contacts with delegations and diplomats from China. "They were trying to establish a link between Wei Su, me, and the consulate," Zhou says.

The FBI put him on a polygraph, Zhou says, and repeatedly asked a single question: "Is Wei Su a spy?" He flunked, they told him, but agents refused to show Zhou his wave graph. "They wanted to scare me into telling them Wei Su was a spy, but of course it wasn't true," Zhou says.

Zhou says he thinks the FBI was tapping his phone when he and Su agreed to meet for dinner in 2011 at the now-closed Sawa Hibachi Steakhouse & Sushi Bar off Route 35 near the Jersey Shore, a meal both men remember for the now-suspect teapot. Su says the FBI agents seemed sure they had a smoking gun after that night.

And yet, after they confronted Su, investigators seemed to back off. Zhou still had to endure multi-hour delays when returning from overseas, as immigration agents searched his electronic devices, he says. Su says he heard nothing from investigators for 2½ years.

In 2015 Su was notified by his boss, Henry Muller Jr., that his security clearance had been suspended because of new "counterintelligence information." Muller, now retired, says he wanted Su to take on a senior technical position once his security clearance was sorted out. But no one at military intelligence would say what the new information was. "I sat across the table from my boss, who was a two-star general, scratching our heads on this," Muller says. "It seemed very nebulous at the time. But that's the way these security guys work. There's nothing you can do about it."

It took 13 months for the Pentagon to issue Su a "Statement of Reason" for his clearance suspension. The classified memo rehashed settled questions from Su's background investigations in 1997, 2002, and 2010, he says. It accused him of enjoying "unexplained affluence" and asked how his family took five vacations in 10 years on a household income of $270,000 a year, according to Su's rebuttal documents. The memo questioned whether he'd received undisclosed funds from China to pay off a mortgage in 2009, two years after visiting the country, and whether one $34,000 deposit in Su's account came from "financially profitable criminal acts." It also accused Su of concealing contacts with two former classmates from China.

Su responded to the allegations line by line. His family vacations to Northern and Southern Europe, Southeast Asia, Mexico, and China were budget tours that came to about $150 a day per person. He documented all his paid-off debts and explained that the $34,000 deposit was a U.S. government check to compensate military homeowners when the Army closed Fort Monmouth in New Jersey and moved Su's command to Maryland's Aberdeen Proving Ground. He enclosed affidavits from past background investigations to prove he had properly disclosed his contacts with Chinese friends.

Six months later, in October 2016, the Pentagon sent a "Letter of Revocation" cancelling his clearance. The final notice dropped the financial allegations but claimed Su failed to fully disclose his classmate contacts in the early 2000s, even after an investigator had put him on "explicit notice" in 2004 that he had to disclose them. After the revocation, Su continued to work on unclassified research, while fighting to clear his name with arbiters at the Pentagon's Consolidated Adjudications Facility, known as the CAF.

In November 2017 he caught a break. The federal Office of Personnel Management, which handled his background investigations for security clearances, reviewed all of Su's documents and agreed to correct several misstatements in the investigators' 2004 and 2010 reports. The amended reports showed Su had appropriately disclosed his classmate contacts. Su sent the corrections to the CAF and retired from the Army at the end of 2017.

Last May he got a short letter from the CAF. Based on the corrected record, it said, the Pentagon's previous letters suspending and revoking Su's security clearance "are not accurate and are hereby rescinded."

"Even now, it's like a nightmare," Su says. "The investigators didn't realize Chinese Americans are Americans, not Chinese."

------

Bloomberg News acquired and analyzed more than 26,000 security clearance decisions made by the Defense Office of Hearings and Appeals (DOHA) from 1996 through October 2019. The cases involved contractors seeking to perform classified work for the Department of Defense and dozens of other federal agencies.

The decisions were gathered via the DOHA website and the Nexis research service. The data include cases published as of Dec. 2, 2019, and exclude appeals cases, which typically do not address specific security concerns.

Among the DOHA decisions, Bloomberg News identified 2,965 cases related to either "Guideline B: Foreign Influence" or "Guideline C: Foreign Preference." Guideline B and C cases represent decisions where security concerns stemmed from an applicant's foreign ties, such as family members living abroad or financial interests in a foreign state.

Bloomberg News also identified the specific country, or countries, flagged in each Guideline B or C case by searching the decision text for the names of 40 commonly-occurring nations, including G20 members and current and historic geopolitical rivals like Iran and North Korea. Russia mentions include references to the Soviet Union.

Each Guideline B or C case was categorized as "granted" or "denied" by parsing the "Formal Findings" section, or the short decision summary, for specific keywords or phrases. Cases where Guideline B or C was mentioned but was not a primary reason for denial were excluded from the Guideline B and C denial totals. If multiple countries were cited in a denial case that also included China or Taiwan, Bloomberg News manually reviewed the case to identify the country most responsible for the denial. To prevent skewing the charts, country-level denial rates were not calculated in years where a country had fewer than five decisions.

Comment: See also: